My first data job was as a data scientist at a clinical trial company in Halifax in 2015. I didn’t love the job and when I started looking for my next role, I discovered a remote-first company called Upworthy which was hiring for a data analyst position. I ended up getting the job, and to my delight the salary was more than double what I was making.

I had stumbled into one of those rare arbitrage opportunities. By working remotely I was able to earn a wage higher than almost anything in my local labour market, and my employer was simultaneously able to save money by hiring a Canadian. Both my employer and I were earning what’s called economic profit because the trade was significantly better than our next best alternative. I was making much more money than I could make locally while Upworthy was paying a lower salary than what would be required to hire an American analyst.

Arbitrage opportunities like this are rare because efficient markets will tend to erode them. If Upworthy was able to save money by hiring in Canada, you’d expect that other firms would do the same, which would drive up the price of Canadian workers until the market reaches equilibrium. The market for remote workers in 2015 was not, however, efficient. There weren’t very many remote companies, and there were lots of complications around hiring outside of your country. This meant that there just wasn’t enough competition in the market to meaningfully change wages.

I was sure that the pandemic would correct this market inefficiency. When large companies shifted to remote work they would realize that there were significant hiring opportunities in Canada, and the administrative costs were small in comparison to the amount of money they’d save on salary. This didn’t happen, and Canadian employees at remote tech companies still earn 30-40% less than their American colleagues before accounting for the high cost of American health insurance. I’ve been in situations where the people reporting to me made significantly more money than me, or where published salary ranges showed a 30% lower price for Canadian employees at the same level.

I can’t figure out why this is happening? Today any US company with remote employees can replace an American worker with a Canadian one, and reduce their labour costs by 30%. Alternatively, US firms can hire elite Canadian talent just by offering their median US wage. If you have the budget for an American Junior Engineer you could turn around and hire a Senior or Staff Engineer for the same price. Why don’t more companies take this bargain?

Why is the market still failing?

I can think of four reasons why this market failure continues.

Bad data

The main culprit behind this market failure is bad data. Most companies localize salaries by buying data from somewhere like the Rand corporation, and comparing their wages to the local market. They will get a single distribution of salaries within a country and target some percentile of that range. This data is often a bit out of date, so in a rapidly changing labour market it is going to give you a lagged number. This creates a kind of drag on how quickly salaries will rise because most firms will be basing their salaries numbers on data that’s a couple of years old.

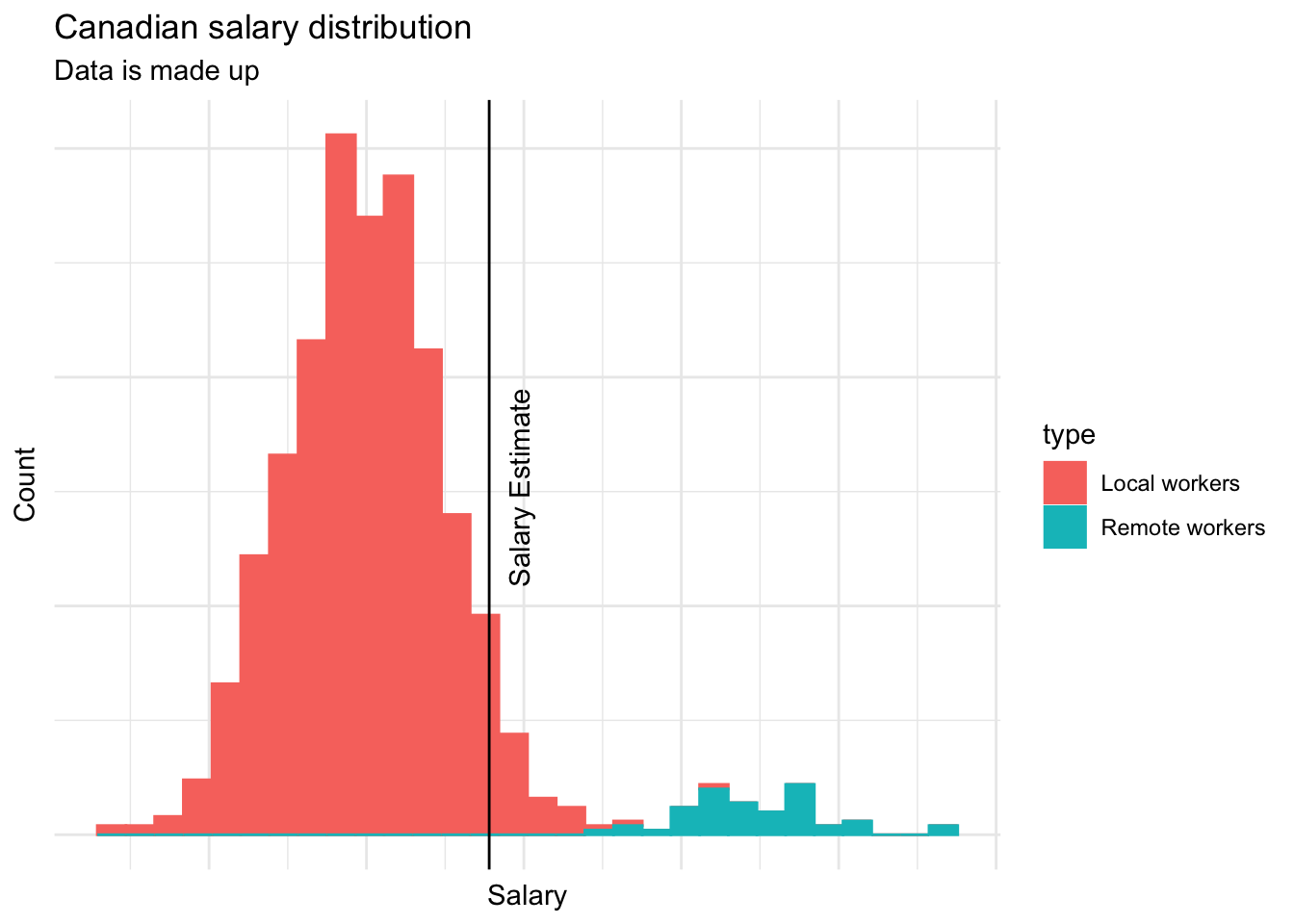

The bigger issue though is that Canadian salaries are bimodal. There’s a large group of people who work for local companies and don’t make that much money, and a smaller group of remote workers who make significantly more. When a company targets the 90% percentile of the global salary range, they will end up with a target salary which low relative to the set of remote workers. Here’s an example of what that distribution might look like, note that while this data is made up it is roughly in line with wages in a place like Nova Scotia.

This supposedly data-driven HR approach has never made sense to me because companies should worry more about profit and productivity than they do about matching a local labour market. If you can profitably hire someone at some salary you should do so even if that salary is higher than their local market. If Canadians really do demand lower wages, then shouldn’t you freeze US hiring and only hire Canadians?

Cheaper offshoring opportunities

One of the problems with Canadian hiring is that people implicitly think of it as a kind of off-shoring. When you think about it this way it doesn’t make a lot of sense because there are much cheaper geographies than Canada. Instead of hiring a Canadian for 70% of what an American makes, why not hire someone from Poland, India, or Brazil for much less than that?

What this analysis misses is that it’s a lot easier to integrate remote Canadian workers than workers from lower income countries. I’ve worked with many off-shore colleagues, and while it’s often wonderful it involves a lot of work. There are often time-zone, language, or cultural communication problems which all require work to overcome. None of these issues are deal-breakers exactly, but it requires investment to set up an off-shore team for success.

Canadians, by contrast, really are indistinguishable from US workers. They typically speak the same language, work in the same time zones, and think about work in the same way. This means that Canadians are substitutes for Americans in ways that other countries are not. In the realm of remote work, distinguishing between a Vancouverite and a Seattleite, a Torontonian and a Chicagoan, or a Nova Scotian and a Mainer, is pretty much impossible. Similarly, the two countries have very similar legal systems, and you never have to worry about a Canadian getting a Visa to attend a company meetup.

This isn’t to say that near-shoring or off-shoring is a bad idea, or that those workers are worse than Canadians, but just that they’re fundamentally different concepts. You can hire Canadians without making any real changes to how your company is organized because they will fit right in to your existing teams.

Information disparities

The second potential reason for the market failure might be information disparity. Workers may not know that working for a US firm is both remunerative and easy, and firms may not know that there is a pool of cheap, high-quality talent north of the border. Similarly hiring based on employee networks or local recruiters reinforces geographic disparities, and means that a firm will pay more than they need to for talent.

Exchange-rate risk

Finally, firms may not hire Canadians because they are worried about exchange-rate risk. At this writing a US dollar buys $1.38 Canadian dollars, which is a big part of why Canadian workers are such a bargain. But what happens if your firm hires a bunch of Canadians and the exchange rate shifts? This worry is overblown in my opinion for a few reasons. First, USD-CAD exchange rates are quite stable, and aside from a brief period in the early 2010s have never been close to parity. Unless there’s a major increase in demand for dirty, expensive, Canadian hydrocarbons, it’s unlikely that the Canadian dollar will ever reach parity with the US dollar.

There are also plenty of ways to structure employment contracts to avoid exchange rate risk. You can of course pay people in USD through a service like Wise, or you can structure the contract to pass exchange-rate risk on to the employee.

For example, you could pay an employee in CAD but offer them a salary structure where 20% of their annual income was distributed as a quarterly bonus. This bonus would be adjusted for exchange rates such that the firm’s US dollar expenditure was constant over the year, while the employee’s take-home pay varied. Finally, in the unlikely event that the exchange rate really spikes, you can always adjust salary, withhold pay increases, or lay people off.

So what’s going on?

I’m generally a believer in markets, and so the fact that there is such a large and persistent gap in real earnings suggests that there’s something about this labour market that I don’t understand. If you have any ideas about what’s going on, or if your company has a unique approach to cross-border hiring, I’d love to hear from you. If you can’t think of any explanations for this apparent market failure, maybe you should consider hiring more Canadians.